Pierre Kjellberg, “La Pendule Française du Moyen Age au XXe Siècle”, 1997, p. 344, pl. B, illustrating a clock of an identical model but dial unsigned.

Pierre Daniel Destigny

Literature

Philippe-Gérard Chabert, “La Pendule ‘au Nègre”, exhibition catalogue April-June 1978, Musée de l’Hôtel Sandelin, Saint-Omer, 1978. Marie-Christine Delacroix, “Les Pendules au Nègre”, in “L’Estampille”, no.100, August 1978.

Jean-Pierre Samoyault, “Pendules et bronzes d’ameublement entrés sous le Premier Empire”, Musée national du Château de Fontainebleau, 1989.

Bernard Chevalier, “La Mesure du Temps dans les Collections de Malmaison, exhibition catalogue May-September 1991.

“De Noir et d’Or, Pendules au bon Sauvage, Collection du Baron François Duesberg”, Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire de Bruxelles, 1993.

“La Pendule à Sujet, du Directoire à Louis-Philippe”, exhibition catalogue June-September 1993, Musée de l’Hôtel Sandelin, Saint Omer.

Pierre Kjellberg, “La Pendule Française du Moyen Age au XXe Siècle”, 1997, p. 344, pl. B, illustrating a clock of an identical model but dial unsigned.

Dominique Paulvé, “Les pendules ‘Au Bon Sauvage’ de Betty et François Duesberg”, in “Connaissance des Arts”, no. 612, January 2004.

Jean-Dominique Augarde, “Une nouvelle vision du bronze et des bronziers sous le Directoire et l’Empire”, in “L’Estampille”, no. 398, January 2005.

Catalogue du Musée François Duesberg, Mons”, 2005. Marie-France Dupuy-Baylet, “Les pendules XIXe du Mobilier National, Faton, Dijon”, 2006.

“Le roi, l’Empereur et la pendule, Chefs-d’œuvre du Mobilier National au Musée du Temps de Besançon”, May-November 2006. Stéphanie Perris Delmas, “La Pendule ‘Au Nègre’ est l’un des Best-Sellers des Arts Décoratifs Français”, in “Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot”, no. 42, December 2008.

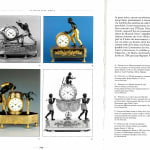

A very fine Empire gilt and patinated bronze Pendule Au Nègre by Pierre Daniel Destigny à Rouen of eight day duration, housed in a superb case by the bronzier Jean-André Reiche, the white enamel dial signed Destigny à Rouen with Roman and Arabic numerals and blued-steel Breguet style hands for the hours and minutes. The movement with anchor escapement, silk thread suspension, striking on the hour and half hours with outside count wheel. The case with dial and stiff leaf bezel housed in a barrel-shaped drum which is seemingly being pushed by a handsome young black workman with thick curly hair, white enamel eyes, bare chest and feet wearing arm bands and a loose fitting trousers, the clock drum and figure upon a rectangular base with chamfered corners, mounted on the front with a collection of barrels, trunk and bundles surmounted by a parrot and anchor and flanked by a pineapple and palm leaves, the ends mounted with parrots, on turned feet

Paris, date circa 1800-05

Height 33 cm, width 27 cm, depth 11 cm.

Like another example of this superb Pendule ‘Au Nègre’, recently acquired by the Musée d’Aquitaine, the subject epitomises late eighteenth century European society’s fascination with the exotic, unadulterated and untamed natural world. This was a notion aired by Jean-Jacque Rousseau, whose ‘Discourse on the Origin of Inequality’, 1754 proposed that beauty and innocence of nature was extended from plants and trees. In 1767 the French explorer Bougainville arrived in Tahiti followed by Captain Cook in 1769. After hearing of the happy and harmonious life of the South Sea islanders, even the brightest wits of London and Paris began to question their own corrupt European society in relation to the innocence of the native islanders. In due course the notion of le bon sauvage was to inspire some of the greatest literary works of the period such as Paul et Virginie (1787) by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre and Atala (1801) by Vicomte de Chateaubriand. In addition to books the concept of the le bon sauvage inspired both the fine and decorative arts and in particular it gave rise to a number of innovative clock cases au Nègre (with African figures) such as this or aux Indiens (with Native American figures).

Within this group were a number of clock cases portraying African men at work; sometimes he would be pushing a wheelbarrow or carrying a bale of cotton on his back while in other instances he was portrayed as a seaman smoking a pipe while leaning against a bale of tobacco leaves. In each of these instances the dial and movement are cleverly integrated into the overall composition. The figure here is shown as a lithe young man, his actions being one of nobility and ease while the frieze below the dial highlights the natural wealth of his native islands and their maritime trading.

The case is one of a number created by Jean-André Reiche (1752-1817) who was one of the leading Parisian bronziers during the Empire period and like Jean-Simon Deverberie, gained particular renown for his Pendules Au Nègre. The son of a shop owner from Leipzig, Reiche was baptised in Leipzig’s Sainte-Nicole Church on 13th August 1752, where his surname was recorded as Reich. Jean-André probably changed his name to accord with French conventions when, like a number of German ébénistes, he moved to Paris where he was received as master founder in June 1785. From his workshop in rue Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth he began specialising in the production of clock cases which especially thrived after the abolition of the guilds during the French Revolution. This meant that Reiche could now create every aspect of a clock case, employing a team of workmen from modellers, casters and chasers to marble workers. His renown immediately grew as a marchand-fabricant de bronzes and especially as a supplier to the Emperor. When he died on 18th March 1817, Jean-André Reiche left his business to his son Jean Reiche, who continued to run it successfully during the Restoration period.

Pierre Daniel Destigny (1770-1855), the maker of the clock’s movement, was also of excellent repute. Indeed, he was regarded as one of the leading horologists of his day having made a significant contribution toward the advancement of accurate timekeeping. Born at Sammerville near Troaan, Destigny trained at the Manufacture Royale d’Horlogerie, Faubourg du Temple in Paris before establishing a large factory in Rouen in 1798. As an innovator, Destigny published a number of scientific papers and made presentations to the Académie regarding the perfection of various compensation systems. In 1819 he was awarded a medal at the Paris Industrial Exhibition. Having retired in 1848 aged 78, he died in 1855, three years after the presentation of his final paper titled “Moyen de perfectionnement d’un mécanisme employé pour rendre nulles les influences d’une température variable sur la marche des montres”.