J. Ramon Colon De Carvajal, “Catalogo De Relojes Del Patrimonio Nacional”, 1987, p. 292, no. 278, illustrating a similar clock case but simpler movement in the Spanish Royal Collection.

Comminges

Literature

J. Ramon Colon De Carvajal, “Catalogo De Relojes Del Patrimonio Nacional”, 1987, p. 292, no. 278, illustrating a similar clock case but simpler movement in the Spanish Royal Collection.

Derek Roberts, “Precision Pendulum Clocks”, 2004, p. 100, pl. 31-16, illustrating a table regulator by Autray Fils à Paris, housed in a comparable gilt bronze case.

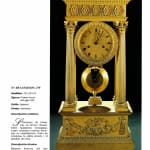

A very fine late Empire gilt bronze table regulator by Comminges à Paris of fourteen day duration, signed on the white enamel chapter ring Comminges Palais Royal N.o 62, the chapter ring with Roman hour numerals and indications for the minutes with blued steel Breguet style hands, the engine turned brass dial centre set with two subsidiary calendar dials, the top one marked 0-31 for the days of the month and the lower with the abbreviated names of the days of the week, both with blued steel pointers. The movement with anchor escapement, striking on the hour and half hour, outside count wheel and a free winging nine rod gridiron compensated pendulum above a large brass bob. The gilt bronze case of architectural form with a stepped rectangular top with anthemion and acanthus as well as egg and dart borders supported on a pair of circular fluted columns with Corinthian capitals, the dial with foliate bezel and drum suspended between the upper parts of columns, the base of each column with a berried laurel leaf band upon a square plinth, both resting on a stepped rectangular base ornamented by egg and dart banding and a foliate border

Paris, date circa 1820

Height 63 cm, width 30 cm, depth 19 cm.

Few clocks by Comminges à Paris and of this design are known. The architectural case compares with many other column clocks of this period but here the columns are distinguished by rare ornate Corinthian capitals. In this respect, it compares with another regulator in the Spanish Royal collection though the latter has a less complex movement. Whilst the case is not signed, its quality and form can be compared to those produced by such eminent bronziers as Pierre-Philippe Thomire or Lucien-François Feuchère and his father Pierre-François Feuchère.

Although Comminges was evidently a fine Paris clockmaker, little is known about this business except that it was listed in the commercial directories of the period as well as in Tardy. The dial notes its address as Palais Royal No 62, while Tardy more specifically lists it at the Galerie de Pierre at the Palais Royal. From about 1830 Comminges was based at Galerie Montpensier and then from about 1839 up until the 1850s it was listed in the Paris trade directories at 47 rue Richelieu. At the time of the clock’s creation, Comminges was based at the Palais Royal, which was a very prestigious location, set within an arcade of galleries that offered a variety of luxury goods for sale. The Palais Royal was in fact built in 1633 for Cardinal Richelieu. Ten years later the buildings were bequeathed to Louis XIV and then passed to the d’Orléans family. Shortly after 1785 the duc d’Orléans (Philippe Egalité) opened its gardens to the public and the buildings to the trade. Jewellers, watch and clockmakers alike were all keen to set up businesses within its precincts. Among them were such distinguished horologists as Leroy who at no 60 Galerie de Pierre, was adjacent to Comminges. Other clockmakers based there included Charles Oudin, while Kinable had also previously operated from under the same roof. It was not only the luxury trades that drew in the public but also the gambling halls; after they were ordered to be closed in 1836 far less people visited the Palais Royal. In turn, many of the former galleries moved to the grand boulevards, which is why Comminges relocated to rue Richelieu.