Ernest Dumonthier, “Les Bronzes du Mobilier National – Pendules et Cartels”, c.1911, pl. 37, illustrating a clock of the same model in the Mobilier National.

Hans Ottomeyer and Peter Pröschel, “Vergoldete Bronzen”, 1986, p. 366, pl. 5.13.3, illustrating a clock of the same model, signed on the dial Galle rue Vivienne à Paris.

Elke Niehüser, “Die Französische Bronzeuhr”, 1997, p. 66 pls. 93-95 and p. 208, pl. 267, illustrating a clock of the same model.

Marie-France Dupuy-Baylet, “Pendules du Mobilier National 1800-1870”, 2006, no. 47, pp. 110-112, illustrating and describing a clock of the same model, with its dial signed Lepaute à Paris, which was delivered in 1805 to the Grand Salon of the Petit Trianon; in 1806 it was at Rambouillet, then in 1832 at the Palais de l’Elysée and today is in the Ministère des Finances.

Claude Galle (attributed to)

Further images

Literature

Ernest Dumonthier, “Les Bronzes du Mobilier National – Pendules et Cartels”, c.1911, pl. 37, illustrating a clock of the same model in the Mobilier National.

Hans Ottomeyer and Peter Pröschel, “Vergoldete Bronzen”, 1986, p. 366, pl. 5.13.3, illustrating a clock of the same model, signed on the dial Galle rue Vivienne à Paris.

Peter Heuer & Klaus Maurice, “European Pendulum Clocks. Decorative Instruments of Measuring Time”, 1988, p. 81, illustrating a clock of the same model.

G. Wannenes, “Le Più Belle Pendole Francesi. Da Luigi XIV all’Impero”, 1991, p. 167, illustrating a clock of the same model.

Elke Niehüser, “Die Französische Bronzeuhr”, 1997, p. 66 pls. 93-95 and p. 208, pl. 267, illustrating a clock of the same model.

Marie-France Dupuy-Baylet, “Pendules du Mobilier National 1800-1870”, 2006, no. 47, pp. 110-112, illustrating and describing a clock of the same model, with its dial signed Lepaute à Paris, which was delivered in 1805 to the Grand Salon of the Petit Trianon; in 1806 it was at Rambouillet, then in 1832 at the Palais de l’Elysée and today is in the Ministère des Finances.

Antoine Chenevière, “Splendeurs du Mobilier Russe 1780-1840”, 2008, p. 188, pl. 193, illustrating an example entirely of gilt bronze in the Monplaisir Palace, Peterhof.

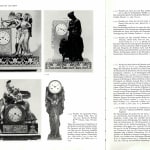

An extremely fine Empire gilt bronze and vert de mer marble mantel clock of eight days duration, housed in a case attributed to Claude Galle representing Hector and Andromache’s final parting. The white enamel dial with Roman and Arabic numerals and inner calendar ring for the 31 days of the month, with a fine pair of gilt brass hands for the hours and minutes and blued steel pointer for the calendar indications. The movement with silk thread suspension, anchor escapement, striking on the hour and half hour on a single bell, with outside count wheel. The case portraying Hector the Trojan prince standing to the left, dressed ready for battle and holding his sword in his right hand and shield in his left which he wraps around his wife Andromache as he bids her a farewell embrace. Andromache, who also leans across the dial, gazes up toward her husband while holding in her arms their infant son Astyanax, who recoils when seeing his father in his soldier’s uniform. The dial within an octagonal drum, on a stepped rectangular vert de mer marble base with a central gilt bronze frieze portraying Hector urging Paris to leave Helen of Troy and join him in battle, while to either side are a pair of seated maidens with a dog and doves, symbolising fidelity and love, the whole on stylised paw feet.

Paris, date circa 1805

Height 63.5 cm, width 51 cm, depth 18 cm.

This dramatic clock case depicts a scene from Homer’s famous epic poem the Iliad that Racine mentions in his Andromaque, recounting the Trojan War, waged by the Greeks against Troy, a city in Asia Minor. It shows the Trojan prince Hector, brother of Paris, bidding farewell to his wife Andromache and their son Astyanax who recoils when seeing his father dressed for battle. The moment is both tragic and moving, for Hector, who has killed Achilles’s friend Patrocles, is about to face the Greek hero in combat. Both he and his wife know that he will die at the hands of Achilles, the son of Thetis. With its theme of bravery, sacrifice, honour and fidelity, this clock case embodies the spirit of the Empire.

Hector, the son of Priam and Hecuba, was a true leader and defender of Troy. During the early years of the Trojan War, he avoided confrontation with Achilles but then decimated the Greek ranks during Achilles’ absence. When the latter’s close friend, Patroclus took up arms he was killed by Hector and thus in retaliation, Achilles killed Hector’s brother Polydorus. Thus, Hector challenged Achilles in a one-to-one combat but was killed. Hector’s dying wishes were for his body to be returned to Priam, but these were ignored. Instead Achilles attached his body by the ankles to his chariot and rode in triumph around the city walls, watched from the battlements by Andromache.

The case is attributed to one of the leading Empire bronziers Claude Galle (1759-1815), while the composition was inspired by a biscuit porcelain group Les Adieux de Hector et made by Sèvres under the direction of Louis-Simon Boizot (1743-1809). In addition to examples cited above, clocks of the same model were sold at Kohn, Paris, 23rd June 2014, lot 31 and also in the Robert de Balkany, rue de Varenne, Paris sale held at Sotheby’s Paris, 28-29 September 2016, while another example with Viebahn Fine Arts once stood at Villa Hardt, Eltville.

One of the foremost bronziers and fondeur-ciseleurs of the late Louis XVI and Empire periods, Claude Galle was born at Villepreux near Versailles. He served his apprenticeship in Paris under the fondeur Pierre Foy, and in 1784 married Foy’s daughter. In 1786 he became a maitre-fondeur. After the death of his father-in-law in 1788, Galle took over his workshop, soon turning it into one the finest, and employing approximately 400 craftsmen. Galle moved to Quai de la Monnaie (later Quai de l’Unité), and then in 1805 to 60 Rue Vivienne. The Garde-Meuble de la Couronne, under the direction of sculptor Jean Hauré from 1786-88, entrusted him with many commissions. Galle collaborated with many excellent artisans, including Pierre-Philippe Thomire, and furnished the majority of the furnishing bronzes for the Château de Fontainebleau during the Empire. He received many other Imperial commissions, among them light fittings, figural clock cases, and vases for the palaces of Saint-Cloud, the Trianons, the Tuileries, Compiègne, and Rambouillet. He supplied several Italian palaces, such as Monte Cavallo, Rome and Stupinigi near Turin. In spite of his success, and due in part to his generous and lavish lifestyle, as well as to the failure of certain of his clients (such as the Prince Joseph Bonaparte) to pay what they owed, Galle often found himself in financial difficulty. Galle’s business was continued after his death by his son, Gérard-Jean Galle (1788-1846). Today his work may be found in the world’s most important museums and collections including those mentioned above, as well as the Musée National du Château de Malmaison, the Musée Marmottan in Paris, the Museo de Reloges at Jerez de la Frontera, the Residenz in Munich, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.