Pierre Millot

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

Literature

Richard Mühe and Horand M. Vogel, “Alte Uhren – Ein Handbuch Europäischer Tischuhren, Wanduhren und Bodenstanduhren”, 1976, p. 106, illustrating a clock signed on the dial Le Grand à Paris with similar case, featuring the same surmounting figure of Diana but with a musical box below and lacking the lions o the base.

Elke Niehüser, “Die Französische Bronzeuhr”, 1997, p. 200, pls. 63 and 64, illustrating two mantel clocks with a similar surmounting figure but without the lions on the base.

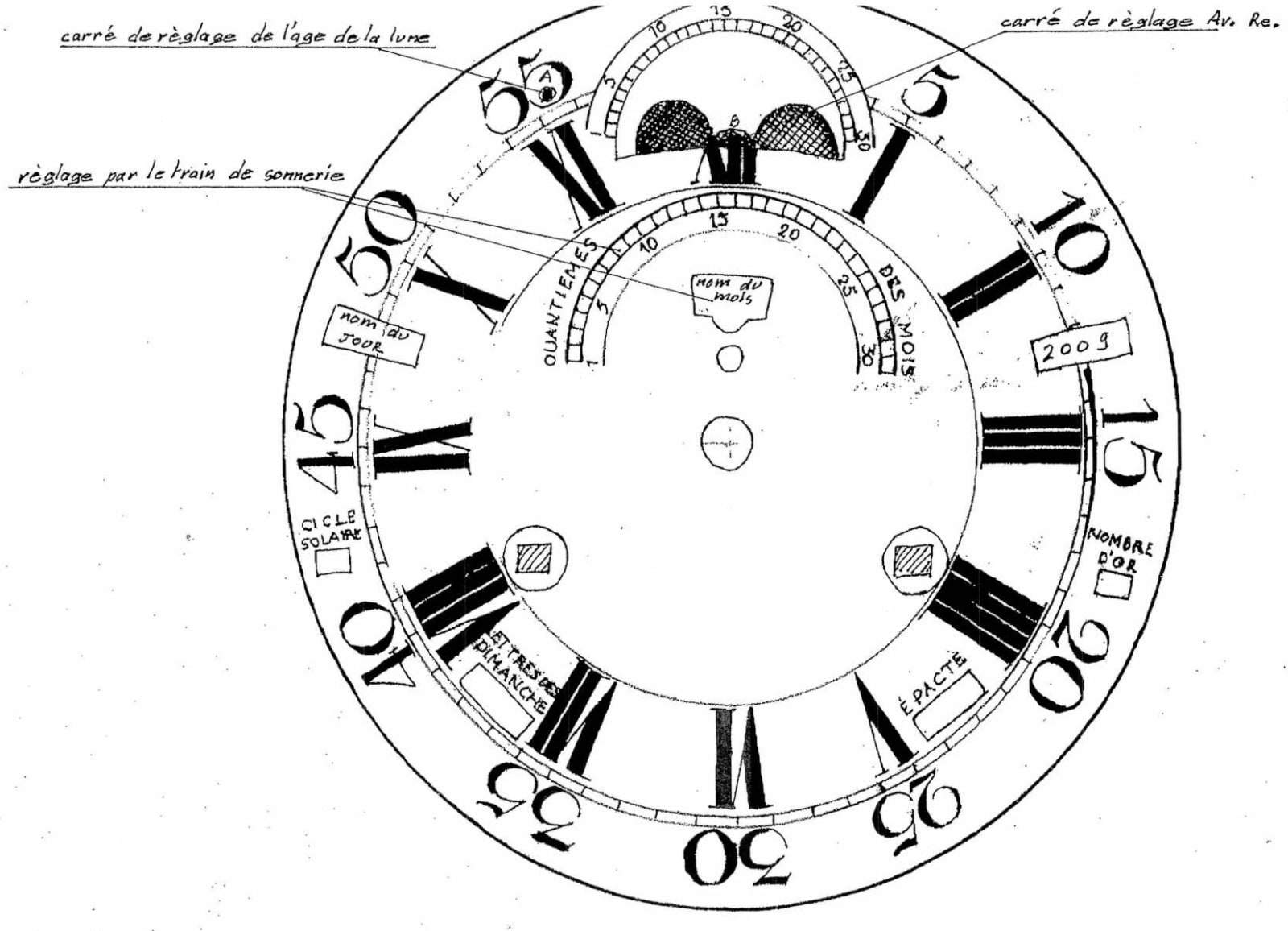

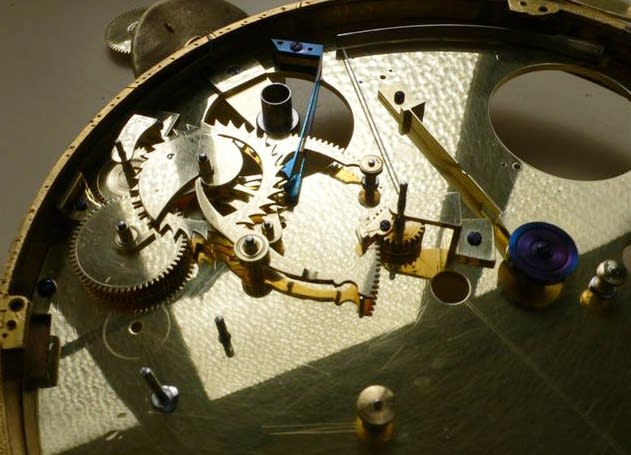

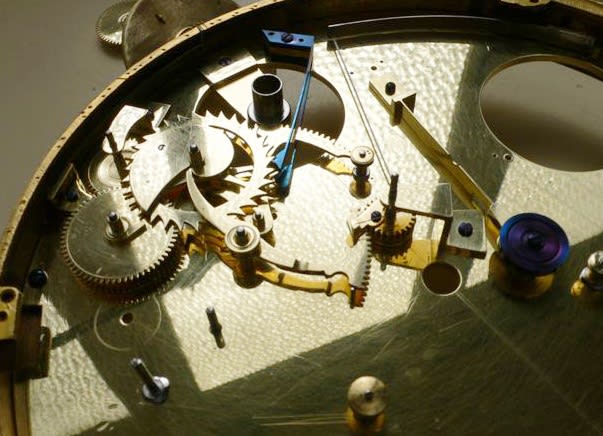

A very rare and highly important Louis XV gilt bronze astronomical calendar mantel clock of fourteen day duration by the esteemed royal clockmaker Pierre Millot, signed on the case either side below the main dial Inv.t & Fecit/ Millot à Paris and housed in a magnificent case attributed to the eminent bronzier Robert Osmond, the white enamel dial with outer minute chapter ring with Arabic numerals and inner hour ring with Roman numerals and a very fine pair of pierced gilt brass hands for the hours and minutes, with a moon phase aperture at 12 o’clock marked above with the 29 ½ days of the lunar month, with a scale below for the regulation of the sonnerie train marked ‘Quantiemes / Des Mois’ with the days of the month indicated by a fine gilt brass pointer, below which is an aperture to indicate the date and names of the months, with various other apertures below to indicate the names of the days of the week, the specific year (with calendar for a thousand years), the solar cycle marked ‘Cicle Solaire’, the golden number marked ‘Nombre d’Or’ and two others marked ‘Lettres des Dimanche’ and ‘Épacte’ with each of the indications corresponding to the ecclesiastical calendar so as to determine Easter and other moveable religious festivals. The main dial also with a winding hole at 11 o’clock for regulating the age of the moon and another winding hole at 12 o’clock for advance and retard. The clock movement with anchor escapement and silk thread suspension. The silvered engraved astronomical dial below the main dial, studded with paste brilliants to symbolise the stars and planets and with one fixed and two moveable shaped shutters below that move according to the length of the night, with a central domed sphere with a sunburst hand and engraved with the world’s main domains, marked 20/40 up to 360 degrees and reading clockwise as follows: 48 Paris / 20. 50 Cracouie/ 40. 38 Tauris / 60. 27 Gomron / 80. 39 Irkin / 100. 14 Siam / 120. 39 Pekin / 140. 31 Ie dujapon / 160. 21 Lamira / 180. 63 Detroit du nord/ 200. 69 Cercle polaire/ 220. 39 C[ercle] des neiges / 240. 19 C[ercle] decorinte /260. 23 Veracrus / 280. 12 Lima / 300. 43 Ie Royal / 320. 25 Mer du nord 340. 27 Ie de fert / 360. The circular glazed door opening to reveal the dial bezel border engraved with the symbols and names of the signs of the zodiac, with apertures to the upper left and right of the latter dial indicating sunrise and sunset respectively marked ‘hres mtes / Lever du Soleil’ and ‘hres mtes / Coucher du Soleil’. The magnificent chiselled and chased symmetrically scrolled-shaped case surmounted by Diana, the moon goddess, holding a radiating sun medallion and wearing a tunic and sandals and seated leaning upon a pedestal amid flowers, foliage and a quiver of arrows beside her, with foliate scrolls around the dials terminated by scrolled feet upon a splayed rectangular plinth mounted by stiff leaves below an oak leaf and acorn border flanked either side by recumbent roaring lions on a pierced Vitruvian scrolled base with a laurel leaf border on scrolled feet

Paris, date circa 1760-70

Height 75 cm, width 48 cm, depth 33 cm.

The importance of Pierre Millot (b. circa 1719 d. after 1785) Horloger du Roi cannot be overstated. He was known for his mechanical brilliance, specialising in clocks with complications and astronomical movements, of which the present example is one of his finest. When Millot presented Louis XV with a similar clock the king, who pursued a passion for such mechanisms and was keen to reward a select few with outstanding talent, gave Millot an allowance and the coveted title Horloger Pensionnaire du Roi. Given its quality, complexity and mechanical ingenuity, it is very likely that this present clock was one that was made for Louis XV, especially as the French monarch, like his court and many subjects, was closely associated with the Catholic church – which was a theme that Millot was fully aware of when he invented and made this clock since it specifically enables its owner to calculate the date of Easter and other annual religious festivals. This was by no means a simple exercise for then as now, the ecclesiastical definition of the date of Easter is that adopted in the year 325 by the Council of Nicaea, convened by the Roman Emperor Constantine, which stated that Easter should fall on the first Sunday after the ecclesiastical full moon following the spring equinox, where the spring equinox is fixed at 21st March. Consequently, the calculation of the date of Easter involved a combination of the 19 year lunar cycle and the 28 year solar cycle. As the calendar drifted increasingly, the spring equinox began to fall within the calendar, progressively earlier each March. By the sixteenth century, the calendar was ten days in advance of the seasons; the lunar phases were equally out of step, since the epacts or épactes (a system indicating the age of the moon at a particular date) were also calculated wrongly. Even though this was a matter of great concern for the Christian world and despite several efforts to revise the calendar, it was not until the sixteenth century that the calendar was reformed and even then it varied from country to country.

In addition to indicating the age of the moon, the solar cycle and dates of the year, complete with a calendar for a thousand years, the clock also incorporates several aspects that enable this computation such as the Golden Numbers (marked ‘Nombre d’Or’) – a numerical sequence from 1 to 19 or 235 lunar cycles, when the state of the moon coincides. Another aperture is marked ‘Épacte’, again a sequence of numbers 1-19 which indicate the age of the moon on 31st December during the preceding year, being the difference between twelve solar months and twelve lunar months at the turn of the year. Another aperture marked ‘Lettres des Dimanche’ indicates Day Letters and Dominical Letters. This system was to determine the days of the week for every single year of the 28 years of the solar cycle in which the 365 days of an ordinary year are marked with one of the seven letters A to G (so-called Day Letters), starting with A for 1st January. These letters remain the same for every year. The letter marking the first Sunday in every single year is called the Dominical Letter, therefore every day having the same letter in that year would be a Sunday. During a leap year, there should be two letters - one for the Sundays before the leap day (or on the leap day), the other for the Sundays after the leap day. Added to the above Millot includes a unique astronomical dial below the main dial featuring a central sphere engraved with the world’s main domains, each marked with their assumed latitude and longitude positions. Encircling the underside of the sphere are three shaped shutters of which two move, according to the length of the lunar cycles, across a night time sky of paste brilliants to simulate the stars and planets.

In essence the clock is a virtuoso of mechanical excellence and ingenuity, which of course is why Millot was and continues to be held in such high esteem. Among his clocks made for the Louis XV and commissioned by the Menus-Plaisirs was one signed as here, Millot à Paris, which was supplied in 1764 to the grand salon at Château de La Muette - the royal hunting lodge in the Bois de Boulogne, favoured by Louis XV to house his mistresses. Two years earlier Millot presented two of his new clocks with half seconds to the Académie des Sciences. Then in 1772 he made another innovative clock again with half seconds sounding on the hours and half hours, with indications for the year, the month, the days of the week and the rising and setting of the sun at Paris, which according to Tardy had a calendar for 9,999 years (although this may in fact have been for 999 years, thus corresponding to the present clock). Jean-Dominique Augarde, in “Les Ouvriers du Temps”, 1996, p. 250 also notes that Millot was possibly the maker of two royal clocks described as “equation clocks, the one solar and the other lunar, decorated with chased bronze gilt in ormolu relating to the sun and moon, with attributes of Apollo and [as here with] Diana…” These were set on superb pedestals by Gilles Joubert and placed in the King’s bedchamber at Versailles 31st May 1763 and were later described in an inventory of January 1791 as ‘Une pendule a seconde dans la boëte de marqueterie richement orné de bronze doré portée sur quatre pieds à griffes de lion et terminée par un vase à bouton de flamme de 7 pieds 2 pouces de haut. Une autre pendule à boussole; le cadran à 24 heures mêmes ornements et terminé par un vase à étoile’. Elsewhere the second clock (with case representing Diana’s attributes) was a planetary clock (according to the Ptolemy system).

Pierre Millot was born at Converpuis near Joinville; by 1742 he was working in Paris as a compagnon and was then received as a maître-horloger on 1st August 1754 by a decree of 25th June that same year. Working from rue Saint-Dominique he enjoyed the patronage of many of the leading figures of his day, not least Louis XV himself but also that of M. Dejean, the marquis de Beringhem, the duc and duchesse de Chevreuse and the duc d’Aumont, whose sale in 1782 included one of Millot’s clocks housed in a gilt bronze mounted veneered case which sold for 584 livres. Today some of Millot’s clocks remain in important private collections and also for instance at Schloss Nymphenburg, Munich, who owns a clock featuring Europa and Bull, signed on the dial Millot Hger Du Roy à Paris. Millot appears to have delighted in complicated movements and thus in addition to those with astronomical movements or equation he also made carillon clocks, i.e. ones that played musical pieces on a series of bells at predetermined intervals. His success brought financial rewards to the extent that Millot was the owner of a country house at Issy where he went in the summer. He continued working until he retired to Sens in 1785. In 1754 Millot married Thérèse Emilie Lefebre by whom he had Jean-Pierre-Nicolas (maître-horloger 1785) and Thérèse-Emilie who married Nicolas Thomas (d. after 1806), who was appointed Horloger du Roi in 1778.

In keeping with his mechanical excellence and royal appointment, Millot only used the finest cases. He is also known to have collaborated with the renowned French Baroque sculptor René Michel (also known as Michel-Ange or Michelangelo) Slodtz (1705-64) for differing case designs and was supplied by the esteemed fondeur-ciseleur Robert Osmond (1711-89, maître 1746), to whom the present case is attributed to, comparing to other examples by this remarkable maker. Among them is one symbolising the Triumph of Music, another crowned by a Chinaman, another by a young putto symbolising Genius and a fourth surmounted by an urn (respectively illustrated in Hans Ottomeyer and Peter Pröschel, “Vergoldete Bronzen”, 1986, pp. 128 and 129, pls. 2.8.17-2.8.19 and p. 542, pl. 1). In addition there is another similarly shaped clock by Robert Osmond surmounted by a young Genius, with movement by Charles André Caron that was made for Madame Adélaïde at Versailles, 1757 and was later owned by the Ministère de l’Intérieur.

Robert Osmond was one of the most prolific as well as one of the most successful fondeur-ciseleurs of his day, working as adeptly in the Louis XV as the Louis XVI styles. Valued by connoisseurs today, as much as in his day, his bronzes were widely distributed by clockmakers and the marchands-merciers. He was born in Canisy, near Saint-Lô and having entered his apprenticeship at a late stage became a maître in 1746 and from 1764 until 1775 worked in association with his nephew Jean-Baptiste Osmond (1742- after 1790, maître 1764). Today Osmond’s work can be found among the world’s finest collections including the Musées du Louvre, des Arts Décoratifs and Nissim-de-Camondo in Paris, the Musée Condé at Chantilly, the Nationalmuseet Stockholm and the Museum of Art Cleveland, Ohio.

As with all of Osmond’s work, the present case is of exceptional quality and of an unusual design to incorporate symbolic reference to both the sun and moon as well as the earth. Firstly, the case is surmounted by a beautiful figure of the mythological deity Diana; she was originally worshipped as the huntress goddess who protected the earth and its wildlife and was later associated with the moon goddess Luna. Wearing her familiar attire of a tunic and sandals and likewise accompanied by such attributes as her quiver of arrows, she points to and holds in her hand a sunburst medallion to symbolise the sun. In this way, the case makes reference to the clock’s intrinsic mechanism which relies on the earth, sun and moon. In addition to the above are other elements such as the oak and acorn sprays, which are often associated with certain members of the Papal family and also represent new life. Then there are laurel leaves which are associated with victory and of course the two lions, the strongest of earth’s beasts who are so often associated with the monarchy and the king’s all powerful rule. Certainly the quality of the clock case combined with its exceptional mechanism makes this clock one that was worthy of a king.