“Catálogo de Relojes del Patrimonio Nacional”, 1987, illustrating a clock of the same model in the Spanish Royal Collection.

Elke Niehüser, “Die Französische Bronzeuhr”, 1997, p. 69, colour pls. 98-100 and p. 243, pl. 912, illustrating an almost identical model with patinated bronze horses and eagle on the clock frieze.

Elke Niehüser, “La Mesure du Temps dans les collections du Musée de Malmaison”, p. 21, description.

Arcadi Gaydamak, “Russian Empire, Architecture, Decorative and Applied Arts, Interior Decoration 1800-1830”, 2000, p. 44, illustrating a gilt bronze clock of the same model with an almost identical frieze mount below the dial but missing the axe heads at each corner.

Hotel De M. J. Onfroy de Breville, Villa Guibert, No. 18, à Paris. Vue d'ensemble du Grand Salon.

See chariot clock left on the fireplace.

Jean-André Reiche (attributed to)

Further images

Literature

Literature: “Catálogo de Relojes del Patrimonio Nacional”, 1987, illustrating a clock of the same model in the Spanish Royal Collection.

Elke Niehüser, “La Mesure du Temps dans les collections du Musée de Malmaison”, p. 21, illustrating a virtually identical clock in the Musée de Château de Malmaison.

Tardy, “Les Plus Belles Pendules Françaises”, 1994, p. 279, illustrating a clock of identical design with an eagle on the frieze below the dial.

Pierre Kjellberg, “La Pendule Française du Moyen Age au XXe Siècle”, 1997, p. 417, pl. D, illustrating a virtually identical clock with movement by Gentilhomme à Paris and eagle on the clock frieze.

Elke Niehüser, “Die Französische Bronzeuhr”, 1997, p. 69, colour pls. 98-100 and p. 243, pl. 912, illustrating an almost identical model with patinated bronze horses and eagle on the clock frieze.

Arcadi Gaydamak, “Russian Empire, Architecture, Decorative and Applied Arts, Interior Decoration 1800-1830”, 2000, p. 44, illustrating a gilt bronze clock of the same model with an almost identical frieze mount below the dial but missing the axe heads at each corner.

“Musée François Duesberg: Arts Décoratifs, 1775-1825”, 2004, p. 37, illustrating two clocks in the Musée François Duesberg of identical design, one with patinated gilt bronze and the other pure gilt bronze horses, one clock signed Blanc Fils, Palais Royal and the other Armingaud l’Aîné à Paris.

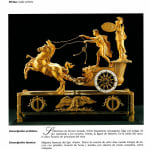

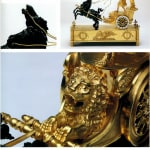

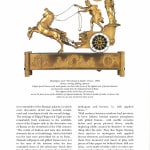

An important Empire gilt bronze chariot clock of eight day duration housed in a magnificent case attributed to Jean-André Reiche after a model by Jean-Baptiste Boyer with Roman numerals and blued steel hands for the hours and minutes set within the wheel of a chariot which is cast at centre with gilt bronze spokes at the 5 minute intervals. The movement with anchor escapement, silk thread suspension, striking on the hour and half hour, with outside count wheel. The magnificent case portraying the figure of Telemachus standing in his chariot which is being pulled by a pair of rearing horses, at the front of the chariot is the head of a roaring lion and at the rear standing behind Telemachus is Athena, the warrior goddess wearing her helmet and holding in her left hand a shield cast with the head of Medusa and in her right hand a spear, the chariot and horses upon a rectangular base mounted on the front with four figures, most probably representing Telemachus, his father Ulysses, Calypso and the nymph Eucharis who sit either side of a tree upon a rock and are flanked at either end by laurel wreaths crossed by a ribbon-tied sword, each end of the plinth with further wreaths and supported at each corner by fasces with upward projecting axe heads

Paris, date circa 1805-10

Height 45 cm, width 49 cm, depth 12 cm.

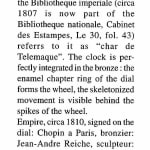

The subject of this superb clock is sometimes incorrectly referred to ‘The Chariot of Apollo’ or ‘Chariot of Diomedes’ however we know its true subject as a design for the model of 1807 by Jean-André Reiche (1752-1817), inscribed Char de Télémaque is in the Bibliothèque National de France, Paris). Among other surviving models of the same chariot clock is one in the Spanish Royal Collection, another in the Musée de Château de Malmaison as well as two further examples in the Musée François Duesberg at Mons in Belgium.

Like many important figural clocks created during Napoleon’s reign, this extremely fine bronze case tells the story of one of the ancient heroes whose valiant acts embodied the spirit of Napoleon’s own Empire. As such it illustrates the adventures of Telemachus, son of Ulysses and his beautiful wife Penelope. According to Homer’s Odyssey Telemachus was persuaded by the gods to go and search for his father after he failed to return home at the end of the Trojan Wars. Since Telemachus’s family tried to keep him at home, Athena, disguised herself as Telemachus’s old guardian named Mentor. Thus Telemachus is shown here riding his chariot, mounted with a lion head to symbolise Fortitude and overseen behind by Athena who wears her usual guise of a helmet and holds a shield and spear.

According to mythology Athena was the daughter of Jupiter which may explain why most clock cases of this design show Jupiter symbolised by an eagle on the frieze below. However here we see further episodes from Telemachus’s life as further recounted in “The Adventures of Telemachus” by the French writer Fénélon. Fénélon’s romance, published in 1699, became a popular source book in the eighteenth century and essentially amplified aspects from the Odyssey. In it he described how Telemachus was shipwrecked on an island that was inhabited by the goddess Calypso, where his father had previously been imprisoned. On seeing him, Calypso fell in love with Telemachus. Venus then sent Cupid to aid her designs but instead Telemachus fell in love with one of Calypso’s nymphs named Eucharis thus enraging the goddess. Cupid also incited another nymph to burn a new boat that Mentor had built and though Telemachus was delighted that his departure had been delayed, Mentor then threw him into the sea where they were picked up by a passing boat.

Telemachus also encountered many other ventures but eventually returned home after finding his father Ulysses. Before the latter was reunited with Penelope Telemachus helped thwart her many suitors that had pursued her during Ulysses’s absence. She too had tried to fend them off by setting them a series of tasks, one of which was to string Ulysses’s bow and shoot an arrow through the handle holes of twelve axe heads. Telemachus was the first to attempt the task at which point Ulysses, who was in disguise, intervened and with the help of Telemachus ousted Penelope’s suitors. This part of the story may explain why the corner of the clock’s base are mounted with fasces - bundles of wooden rods strapped together and enclosing an axe. Although the adventures of Telemachus were diverse the essence of his valiant acts were admirably captured in this innovative clock case. Its maker was Jean-André Reiche who was among one of the leading Parisian bronziers during the Empire period. The son of a shop owner from Leipzig, Reiche was baptised in Leipzig’s Sainte-Nicole Church on 13th August 1752, where his surname was recorded as Reich. Jean-André probably changed his name to accord with French conventions when, like a number of German ébénistes, he moved to Paris where he was received as master founder in June 1785. From his workshop in rue Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth he began specialising in the production of clock cases which especially thrived after the abolition of the guilds during the French Revolution. This meant that Reiche could now create every aspect of a clock case, employing a team of workmen from modellers, casters and chasers to marble workers. His renown immediately grew as a marchand-fabricant de bronzes and especially as a supplier to the Emperor. When he died on 18th March 1817, Jean-André Reiche left his business to his son Jean Reiche, who continued to run it successfully during the Restoration period. Among many other celebrated clock case models by Jean-André Reich is one known as La Lecture or The Reader portraying a young girl at a desk, of which there is an example in the British Royal Collection. In addition to subjects taken from everyday life as well as those inspired by mythology Reiche, together with Jean-Simon Deverberie, was particular renowned for his Pendules Au Nègre.

Elke Niehüser and others note that the model for this clock case was most probably by the sculptor Jean Baptiste Boyer (1783-1839), who worked in the grand classical manner. Born at Grandpré in the Ardennes, Boyer trained under the leading Neo-classical sculptor Jean-Guillaume Moitte. In 1824, when living at rue Saint-Denis, Boyer made his debut at the Paris Salon with a plaster model of Zéphir contrariant les amours d’un papillon et d’une rose (Zephyr Frustrating the Courtship of a Butterfly and a Rose) which he later executed in marble for the Salon of 1827.