THE GOLDEN AGE OF FRENCH WATCH AND CLOCKMAKING CIRCA 1740-1830

Since pre-historic man made the first sundial, civilisation has felt a need to record time. During the Seventeenth, Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Centuries, this simple desire evolved into an increasingly complex science and art, to produce time pieces of exceptional design and detail, high finish and excellent astronomical movements. Towards the end of the Eighteenth Century, the Dutchman, Christian Huygens developed the pendulum and spiral balance spring which were to transform the whole science of horology. His innovations were readily adopted by the English makers, thereby establishing their superiority in the new field of accurate time keeping. England's supremacy, c.1660-1740 was initiated by the work of Thomas Tompion, Daniel Quare, Joseph Knibbs, Edward East, George Graham, John Harrison and others whose work raised mechanical clockmaking to unparalled heights. They were followed later by other notable horologists, including Eardley Norton. John Ellicott, Thwaites and Reed, John Arnold and others such as Marwick Markham, Christopher Gould, Francis Perigal and Edward Prior, who made some extremely fine clocks for the Turkish and Middle Eastern market.

The English clockmaking trade was seriously undermined when in 1797, Parliament levied a tax of five shillings on all new clocks. At the same time Louis XIV ensured that French makers were enjoying a lavish patronage. France's "Golden Age", c.1740-1830 was initially propelled by Julian Le Roy. His example of fine craftsmanship and superior design did much to raise the whole status and standard of French horology. Julian Le Roy was followed by many others, notably his son, Pierre Le Roy, Jean-Antoine Lepine, Jean-André Lepaute, Robert Robin, Antide Janvier, Ferdinand Berthoud and Abraham-Louis Breguet. Their superior craftsmanship, high finish and ingenuity ensured that by the mid Eighteenth Century, France had become the leading clockmaking nation. At the same time the demand for ever more accurate time keeping, particularly for astronomical and maritime use, resulted in several important inventions.

From the mid Sixteenth Century and up until the Revolution, French clockmaking was heavily governed by the guilds, intended to control quality as well as protect members rights and privileges. The various guilds closely controlled the division of labour; clockmakers were allowed to work in gold and silver without recourse to a goldsmith but had to employ independent craftsmen when using other materials. Before the reign of Louis XIV this was not important as French clocks were made wholly of metal. However during the Eighteenth Century, French case making became so sophisticated that several workers were involved; an ebenist, a stonemaker or a caster and metal gilder, with the clockmaker having overall control of the final appearance.

The English considered the maker of the movement was paramount, while the French placed equal emphasis on both the clock and its case maker. The design of French clocks, unlike the Englich closely corresponded to contemporary furniture styles. Decorative French clocks were considered an important furnishing accessory and the demand for such pieces steadily increased throughout the Eighteenth Century. The beginning of the century corresponded with the advent of the Regence or early rococo style with lighter and gayer forms superseding the grander architectural forms of Louis XIV clock cases. The height of the rococo, 1730-1750, described as the Louis XV style was characterised by asymmettrical design, bright colours and naturalistic motifs. In keeping with these principals case makers introduced a number of different materials. Bronze became increasingly popular, used either as an alternative to wood or as a decorative finish, ormulu in conbination with porcelain was also popular. Toward the mid Eighteenth Century, French clock cases were decorated with the newly deweloped and brightly coloured, vernis martin, an imitation Oriental lacquer; while horn, first introduced during Louis XIV's reign, was now often painted. The Louis XV period saw the intoduction of the cartel or wall clock, which was never favoured in England, toward the end of the period, clocks were often supported by animals or grotesques.

From the 1750's the exuberance of the rococo was replaced by simpler classical ornament, inspired by recent Antique excavations. Antique decoration prevailed throughout the Louis XVI period and continued during the Directoire and Empire periods. Classicism inspired the production of new clock models such as the lyre, the vase, urn or the temple. The most popular model was the subject or figure clock, a clock set within an elaborate sculptured case. Subjects were inspired by Greek or Roman mythology, themes such as science, music and art. Nationalism was important, symbolised by the continents or battle victories such as Napoleon's campaigns into Egypt. Some subject clock cases were of carved marble though the majority were of cast gilt bronze reaching perfection tn the hands of Pierre Gouthiere or Pierre-Philippe Thomire. This type of clock proved an inspiration to later German, Austrian and even American clockmakers.

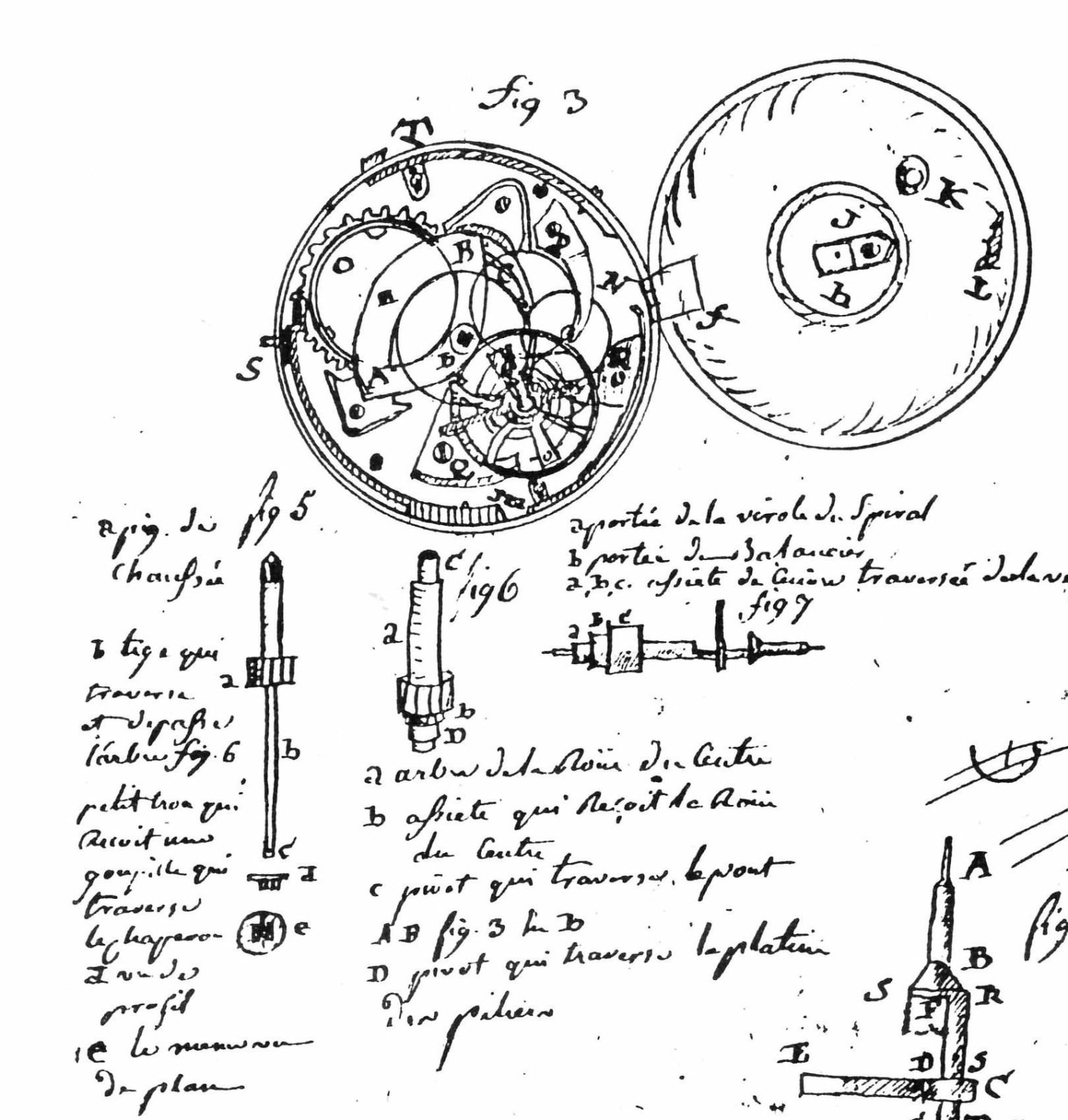

A noticeable division between decorative and scientific clockmaking emerged after c.1750. While many eminent makers continued to adorn furnishing clocks in elaborate casings they also intoduced new types of clocks which relied purely on scientific and mechanical craftsmanship. The skeleton clock was a notable example which left visible all mechanical details. Pierre Le Roy, Berthoud, Robin, Lepaute, Breguet and Janvier were among the finest to produce such pieces/They also introduced the precision regulator and chronometer. Like the skeleton clock these were sparse in detail but attained an aesthetic quality to equal some of the most decorative time pieces.

The Louis XVI period marked France's finest horological age; there was a significant increase in clock production as well as diversity in case design but above all, a specific advance in mechanical and scientific discoveries. However France had already led the world since c. 1740 and continued to do so for nearly a century During this period the English and other European nations, notably Switzerland, Holland, Italy and Austria also produced some extremely fine time pieces. By the mid Nineteenth Century the differences between national styles and the struggle for dominant rank had begun to plateau. France, however could remain assured that its pre-eminent reputation during its earlier "Golden Age" would never be forgotten. Time pieces from this period can be found among the world's major museums and private collections, and continue to be sought by a progressive range of collector.