Ernest Dumonthier, “Les Bronzes du Mobilier National, Pendules et Cartels”, 1910, p. 5, illustrating a design from 1790 by Jean Démosthène Dugourc for a chimney piece for the bedroom of Madame Adélaïde which shows a clock of the same model in central position on the mantelpiece.

Hans Ottomeyer and Peter Pröschel, “Vergoldete Bronzen”, 1986, p. 297, pl. 4.18.5, illustrating a similar clock with case by Pierre-Philippe Thomire and dial signed Sauvageot à Paris.

Tardy, “Les Plus Belles Pendules Françaises”, 1994, pp. 184-5, illustrating a similar clock by Pierre-Philippe Thomire with movement by Robert Robin with Sèvres porcelain plaques in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.

Jean-Dominique Augarde, “Les Ouvriers du Temps”, 1996, p. 240, pl. 189, illustrating a similar clock with case by Pierre-Philippe Thomire with Sèvres plaques and movement by Robert Robin in the Corcoran Gallery, Washington.

Pierre Kjellberg, “Encyclopédie de la Pendule Française du Moyen Age au XXe Siècle”, 1997, p. 266, illustrating the example in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.

Pierre Kjellberg, “Encyclopédie de la Pendule Française du Moyen Age au XXe Siècle”, 1997, p. 267, illustrating a very similar clock signed on the dial Manière à Paris.

Giacomo et Aurélie Wannens, "Les plus belles pendules françaises, de Louis XIV à l'Empire, p. 197

Jean Nérée Ronfort & Jean-Dominique Augarde.

A l'ombre de Pauline. La Résidence de l'Ambassadeur de Grande-Bretagne à Paris. P 50, plate 22.

Edition du Centre de Recherches Historique. Paris, 2001.

Ambasse D'Angleterre, Rue Faubourg Saint-Honoré, no. 39, Pendule signée THOMIRE.

Pierre-Claude Lépine (Raguet-) French, 1753-1810

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 13

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 14

)

Provenance

Jean Grillon des Chapelles (1732-1813). Amador-Jean-Pierre Grillon des Chapelles (1768-1853), son of the latter and thence by descent and remaining at Château des Chapelles, Indre until recent years.

Literature

Ernest Dumonthier, “Les Bronzes du Mobilier National, Pendules et Cartels”, 1910, p. 5, illustrating a design from 1790 by Jean Démosthène Dugourc for a chimney piece for the bedroom of Madame Adélaïde which shows a clock of the same model in central position on the mantelpiece.

Hans Ottomeyer and Peter Pröschel, “Vergoldete Bronzen”, 1986, p. 297, pl. 4.18.5, illustrating a similar clock with case by Pierre-Philippe Thomire and dial signed Sauvageot à Paris.

Tardy, “Les Plus Belles Pendules Françaises”, 1994, pp. 184-5, illustrating a similar clock by Pierre-Philippe Thomire with movement by Robert Robin with Sèvres porcelain plaques in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.

Jean-Dominique Augarde, “Les Ouvriers du Temps”, 1996, p. 240, pl. 189, illustrating a similar clock with case by Pierre-Philippe Thomire with Sèvres plaques and movement by Robert Robin in the Corcoran Gallery, Washington.

Pierre Kjellberg, “Encyclopédie de la Pendule Française du Moyen Age au XXe Siècle”, 1997, p. 266, illustrating the example in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris and p. 267, illustrating a very similar clock signed on the dial Manière à Paris.

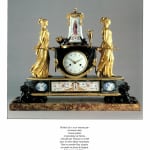

A highly important Louis XVI gilt and patinated bronze and white marble mantel clock of eight day duration representing the Vestal Virgins Carrying the Sacred Fire, with movement by Pierre-Claude Raguet-Lépine housed in a magnificent case attributed to Pierre-Philippe Thomire, signed on the white enamel dial Lépine/ Her. Du Roy [later defaced] Place des Victoires and also signed and numbered on the movement Lépine hger du Roy à Paris/ no 4276. The dial with Roman and Arabic numerals with inner red numbering for the 31 days of the month with a fine pair of pierced gilt brass hands for the hours and minutes and pierced blued steel hand for the calendar indications.

The movement with anchor escapement, silk thread suspension, striking on the hour and half hour on a single bell, with outside count wheel. The case with a pair of Vestal Virgins carrying a draped casket housing the clock itself surmounted by a flaming tripod brazier on sphinx supports, headed by ram’s heads and flanked by a tazza and pitcher, the figures and casket on a shaped rectangular white marble plinth with rounded ends centred by a gilt frieze cast with putti playing flanked by square plaques mounted with the figures of Calliop to the left and Uranie to the right, supported on four reclining lions resting on a rectangular white marble base

Paris, date circa 1785-90

Height 64 cm, width 53.5 cm, depth 18.5 cm.

Sixteen examples of this model are known including examples cited above as well as one in the Minneapolis Institute of Art (supported on leopards instead of lions) as well as two others in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Five of the known examples are decorated with Sèvres plaques, one of which was included in the 1793 inventory of clocks belonging to Marie-Antoinette; it was delivered to the Queen for her boudoir at Château de Saint-Cloud in 1788 by the marchand-mercier Dominique Daguerre and is now in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris. Another with a movement by Robin is in the Corcoran Museum while another with movement by Pierre-Claude Raguet-Lépine was recorded in New York with the Dalva Brothers. There are two examples with an imitation Wedgewood frieze on the base and movement by F. L. Godon, clockmaker to the King of Spain, one of which was delivered to the Queen’s sister the duchesse de Saxe-Teschen while the other is in El Museo Nacional des Artes Decorativas, Madrid.

The assumption that the marchand-mercier Dominique Daguerre owned the model is confirmed by a corresponding description in the inventory drawn up after his death which notes: ‘X une autre pendule dite les porteuses mouvement ajusté dans une espece de brancart surmonté d’un petit autel le tout en bronze doré au mat et porté par deux figures de femmes en bronze de couleur antique avec socle de marbre blanc à bas relief porté par quatre roues en bronze noir et sur double socle en marbre bleu turquin’.

The attribution to the pre-eminent bronzier Pierre-Philippe Thomire (1751-1843) is confirmed in an article by Alvar González-Palacios in “Connaissance des Arts”, September 1976, pp. 11-13, in which he cites Pierre Verlet, who discovered documents from the Sèvres porcelain factory 1788 which note that all the aforementioned mounts for Marie-Antoinette’s clock were provided by Thomire. Furthermore González-Palacios cites other very similar models that are signed by Thomire such as one formerly owned by Pauline Bonaparte-Borghese (now in the British Embassy, Paris). It is believed that all other models of this clock were executed by Thomire. The model itself was derived from an engraving after Hubert Robert, published by the Abbé de Saint-Non in “Recueil des Griffonis”, 1771-73. Jean Démosthène Dugourc (1749-1825), one of the most famous French draughtsmen working in ornamental design during the second half of the eighteenth century is known to have completed a design in 1790 for Madame Adélaïde’s bedroom, featuring a clock of identical design at centre stage (reproduced in Dumonthier, see above).

The clock itself was made by the royal clockmaker Pierre-Claude Raguet, known as Raguet-Lépine (1753-1810), who was in many respects just as successful and as illustrious as his father-in-law Jean-Antoine I Lépine (1720-1814) with whom he worked in close association and whose business he succeeded in 1784. Born in Dôle, Pierre-Claude married Jean-Antoine’s daughter Pauline in 1782, having already invested 16,000 livres in his future father-in law’s business, he then purchased a third share in 1783 and finally took over the business in June 1784 under the name of Lépine à Paris, Horloger du Roi. Prior to this he had worked as a compagnon to Jean-Antoine I Lépine, then in 1785 he was received as a maître and by the following year was established at place des Victoires (the address on the present dial). Lépine-Raguet not only became prosperous from his clock productions but also dealt in diamonds and precious stones. His clocks and watches were of the highest quality and as such were supplied to the cream of society, including the comte de Provence and Louis XV’s daughters at Château de Bellevue. He was also a member of the jury responsible for deciding upon a new Republican time system (1793); during the Empire he was appointed Horloger breveté de Sa Majesté l’Impératrice-Reine, 1805 and four years later was titled Horloger d’Impératrice Joséphine while his other clientele included Napoleon I, Jérôme King of Westphalia, Charles IV King of Spain, the princes Talleyrand, Kourakine (the Russian Ambassador) and Schwarzenberg (the Austrian Ambassador).

Such was his success that he needed a large workforce which included a number of his relatives including Jean-Antoine II Lépine, who managed the workshop as well as Jean-Louis Lépine in Geneva and Jacques Lépine in Kassel, Germany. As here his cases were supplied by Pierre-Philippe Thomire and by other leading bronziers such as F. Rémond, F. Vion, E. Martincourt, the Feuchères and Duports while his dials were supplied by such fine enamellists as Coteau, Dubuisson, Cave, Merlet and others. Today Raguet-Lépine’s work can be admired in such collections as the Musée du Louvre, Château de Compiègne, the British Royal Collection, Musée International d’Horlogerie at La Chaux-des-Fonds, Deutsches Uhrenmuseum Furtwangen, Schloss Wilhemshöhe Kassel, the Patrimonio Nacional in Spain, the Hermitage Saint Petersburg as well as the Detroit Institute of Arts and Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

A fascinating aspect concerning the clock’s history is that the dial originally showed the words “Hger du Roi” (clockmaker to the King) which were then defaced though are still just visible. Their removal would probably have occurred during the Reign of Terror when both clockmakers and owners of such items were keen and were encouraged to disassociate themselves from any former royal connections. The creation of such a clock would have taken several years, the case having been made by Thomire and supplied to Lépine well before the Reign of Terror, as was the movement but the final assembly would only have taken place when a suitable order for such a luxury item came. In this instance one can assume that the commission came from Jean Grillon des Chapelles (1732-1813) who during the Revolution was happy to distance himself from any former royal associations.

The importance of the clock not only rests upon its beauty and quality as well as its design and makers but also its history especially as unlike so many other eighteenth century luxury pieces it has remained in the same family until very recently. Born in Chateauroux 1732 and baptised in December that year, Jean Grillon des Chapelles came from a family of wealthy silk merchants and was the son of Rene Grillon (1685-1747) and Marie née Rabier. Having studied law in Paris he was then appointed an avocet au parlement in Paris 1764. The following year he married Amador-Thérèse Delarue (1741-77), daughter of Pierre Delarue, one of the King’s Secretaries. As a payee of rents to the Hotel de Ville in Paris, during the Revolution he then renounced all former associations with the royal family and made his fortune by overseeing supplies to the army. At about this time he purchased the ancient Hôtel de Charollais and then the Hôtel belonging to the heirs of Lebas de Courmont in la rue d’Anjou Saint-Honoré. In 1803 he gave the furnishings from the latter home to his children. An inventory drawn up in 1814, the year after Jean Grillon des Chapelle’s death, lists this clock which valued at 500 francs was the most expensive piece within the collection and appears to have been placed on the mantelpiece in the grand salon. As the most valued work, the clock was kept by his eldest son Amador-Jean-Pierre Grillon des Chapelles (1768-1853), who moved it to Château des Chapelles where it remained until very recent years, having been passed down through the various generations of the family. In 1943 an inventory was made of the castle in which this clock was listed as “une pendule bronze patiné et doré socle marbre blanc de LEPINE 12000 francs”. Among other very fine pieces from the same important collection was a Louis XVI commode en secrétaire by Jean-Henri Riesener which was sold in Paris, 15th December 1923, lot 5.

JEAN-ANTOINE LEPINE (1720-1814). FRENCH

Jean-Antoine Lepine combined perfect technical quality with aesthetic design. He was appointed clockmaker to Louis XV and Louis XVI, for whom he made 20 clocks. His firm also made clocks for Napoleon, one of which is in the Palais de Compiegne, while another for the Empress Josephine is in the Mobilier National, Paris. Lepine was also patronised by the Spanish and English royality, three Lepine mantle clocks and an astro clock are housed at Buckingham Palace, London. In addition, Lepine time pieces can be found in the Victora and Albert Museum and the Guildhall, London; the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambride; the Carnegie Museum; the National Museum of Stockholm; Basel Museum; Mathematische Physikalische Salon, Dresden and Geneva Horological School.

The son of Jean Lepine, a mechanic who made music boxes for Louis XVI, Jean-Antoine was born in Gex, France. He served an apprenticeship under Decrose of Grand Sacconex, Switzerland. By 1744 Lepine was established in Paris, working for Andre Charles Caron (1697-1775).In 1756 he married Caron's daughter and was promptly made a partner. The firm of Caron et Lepine at Rue St.Denis continued until 1769, when Lepine succeeded the elder.During the 1770's he also acted as an agent for Voltaire's workshops at Ferney, near Geneva. In 1772 Lepine transferred his Parisian business to Place Dauphine, by 1778 he was operating from Quai de l'Horlogue and from 1781-87 at Rue aux Fosses. He was joined by his son in law, Claude Pierre Raguet (1753-1810), who took over the business, 1783. In 1810 the firm was sold to J. B. Chapuy, who among others employed Jacques Lepine (nephew of Jean-Antoine). The firm continued to prosper under various owner, trading under the name of its founder until 1916.

The development of watch and clock making is indebted to Lepine's technical innovations, his most notable, c. 1760 was the Lepine calibre which resulted in the production of the first genuinely thin watch. The Lepine calibre was soon accepted and developed by other French watchmakers, notably A. L. Breguet (1747-1823). However it was not adopted in England , so while the demand for "thin" watches increased, French watchmakers soon established a pre-eminence. The Lepine calibre is now a universal movement in all watches. Lepine continued to perfect the internal design of his "thin" watches so that parts were more accessible for repair and maintenance. These watches were highly prized, in 1781 he was selling them for £ 840 a piece. Lepine also introduced other innovations such as a watch that wound by a push-piece.

Lepine was also at the forefront of design, and with Breguet was one of the first to use Arabic numerals, for a period he used a combination of both Arabic and Roman figures, but by 1789 his firm had returned to Roman numeration. Lepine developed a unique decoration, surrounding the number 1 with a circle to create an aesthetic balance with the number 11; it appears that he was the only watch and clockmaker to do so The Lepine firm employed some of the finest craftsmen to create fashionable and decorative cases such as Nicolas Petit who created sumptous cases in the Louis XVI style. Thus while Lepine placed emphasis on design he and his firm also aspired toward mechanical excellence.

Copyright by Richard Redding, Zurich. All rights reserved!