Charles Topino

Further images

Literature

Alexandre Pradère, “French Furniture Makers”, 1989, p. 318, illustrating another secrétaire à abattant stamped Topino of circa 1780 of very similar overall form but with marquetry work and raised on block feet as well as having a pierced gilt bronze frieze (sold by Christie’s 3rd July 1986, lot 117).

Pierre Kjellberg, “Le Mobilier Français du XVIIIe Siècle”, 1998, p. 846, illustrating a marquetry secrétaire à abattant by Topino, similar in design to the latter as well as the present example.

Thibaut Wolvesperges, “Le Meuble Français en Laque au XVIIIe Siècle” 2000, pl. 181, illustrating a commode-secrétaire by Topino of circa 1785, decorated with Chinese gold and black lacquer.

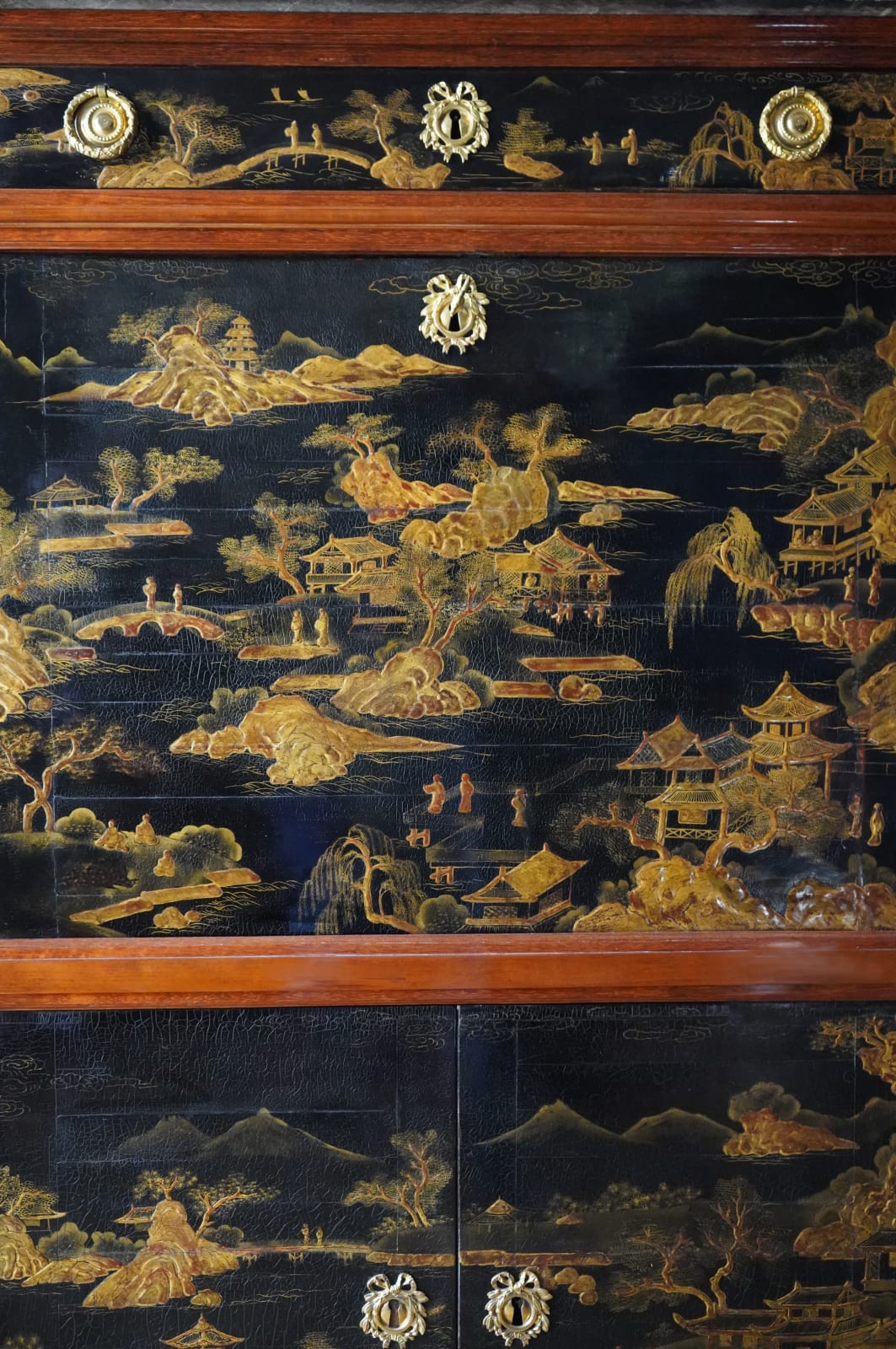

An extremely fine Louis XVI gilt bronze mounted solid satinwood Chinese black and gold lacquer secrétaire à abattant by Charles Topino, stamped C Topino JME on the top, surmounted by a grey veined marble top with projecting canted corners above a frieze drawer which like the doors below as well as the three panels to the sides is decorated with very fine Chinese black and gold lacquer work displaying figures often seen walking in pairs in a landscape with clouds above, mountains in the distance, sailing vessels on the water, bridges crossing a river, pagodas and other buildings as well as willows and other sinuous trees. The frieze drawer centred by a ribbon-tied foliate escutcheon with a circular beaded handle to the right, the frieze drawer above the fall-front door with a comparable central escutcheon, opening to reveal a gilt tooled green leather writing slide while inside are three sets of drawers either side of a central cubby hole and above that a divided shelf and a further single shelf. The fall front above two doors each with a ribbon-tied escutcheon. Flanking and dividing the lacquer panelled drawers and doors is plain satinwood, with canted fluted corners and below a plain base with conforming canted corners

Paris, date circa 1775-85

Height 140, length 89 cm, depth 41 cm. Dimensions of the marble top: length 94 cm, width 43 cm.

Whilst Charles Topino (c. 1742-1803) is best known for his outstanding marquetry work, he occasionally ornamented his high-quality furniture with Oriental lacquer work, as we see here. Again, as here he tended to favour light coloured woods such as satinwood which provides a perfect contrast to offset the bold Chinese black and gold lacquer. Topino tended to specialize in making light furniture such as small tables, chiffonnières and bonheurs-du-jour although he is also credited with outstanding commodes and secrétaires in both the Transitional and full Louis XVI styles. Such pieces were distinguished by their high quality, for which he gained great acclaim. Whilst he occasionally employed Oriental lacquer, the majority of his pieces were inlaid with fine marquetry. These fell into two categories. The first often featured a still-life featuring items such as vases, teapots, bottles and other artefacts such as cards but less rarely Chinoiserie landscapes, of which the latter were inspired by Coromandel lacquer screens that were particularly fashionable during the 1770s and early 1780s. Topino’s second type of marquetry work comprised floral garlands and bouquets highlighted on a pale wood ground of citronnier or yellow-stained maplewood, generally found on furniture between 1775-80. He also occasionally combined geometric marquetry with these two main types of decoration. Many of his pieces were further ornamented with sumptuous gilt bronze mounts, which were often cast by Viret, chased by Chamboin and Dubuisson and gilded by Bécard as well as Gérard and Vallet.

Topino worked for a number of years as an independent craftsman before he was received as a maître in 1773. His father Henry-Nicolas Topino-Lebrun, who also appears to have worked as an ébéniste, was in Paris 1763 but by 1774 was living in Arras. From 1757 Charles Topino worked in the rue du Faubourg-Saint-Antoine gaining great renown as a marqueteur. Although Topino supplied distinguished clients from the French aristocracy, his daybook for the years 1771-79 suggests that he actually had very few private clients. Instead, his main customers were the marchand-merciers and marchand-ébénistes, notably Héricourt, Dautriche, Migeon, Denizot, Moreau, Delorme, Tuart, Joubert and Boudin. In particular he is known to have supplied the latter with marquetry and lacquered light tables as well as bonheurs-du-jour. He sometimes sold complete pieces to all the above and at other times just provided them with marquetry panels.

As evidence of the high esteem in which he was regarded, in 1782 Topino was elected député of his guild. The guilds played a dominant role in eighteenth century Paris and imposed strict regulations by insisting upon a high standard of quality and also by restricting exactly what each master craftsmen were allowed to make, hence a maître-ébéniste was not allowed to create bronze mounts which could only be produced by a master bronzier. The guilds also regularly inspected the Parisian ébénistes, often as much as four times a year, and as a sign that they approved the quality of a piece of furniture, they would stamp that particular piece with the letters JME – as we see here after Topino’s own stamp. The letters JME stand for jurande des menuisiers-ébénistes and would only be added once a committee, made up of elected guild members, had approved the quality of each item. If however the piece was considered of inferior quality it would be confiscated. In essence the stamp JME was a mark of approval. But despite this and the prodigious quality of Topino’s work, he appears to have had considerable financial worries and was eventually declared bankrupt in December 1789. According to Salverte, his financial affairs were very disorganised and were made even worse by the French Revolution. His financial concerns may also have been compounded because of his moderate pricing, although today Topino’s work commands very high figures and is highly sought after.

Examples from his oeuvre were included in the Earl of Rosebery’s former collection at Mentmore House (sold in 1977) and also remain in the Rothschild Collection at Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire. Other pieces can be found at the Musées des Arts Décoratifs, du Louvre, Nissim-de-Camondo in Paris, also at the Lambinet Versailles, Château Champs-sur-Marne, Rouen, Ephrussi at Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat and Cincinnati Art Museum.